The list can operate in different ways: as a cultural tool, a poetic mechanism or a communicative system. Its definition is multifaceted. Still, it remains necessary to determine from which perspective we look at, which approach to adopt for the study of this subject to be able to handle it and convey a clear and relevant analysis. How can this seemingly naive form be studied? Firstly, it seems necessary to question the information value of a list. In a fundamental sense, a list has no proper meaning: it always refers to a context and takes shape from the content it contains. It is thus essential to analyse the list in relation to something, and therefore to analyse its function within that specific context. Hence, this research focuses on the list functions instead of looking at a specific type of list. In the book List Cultures: Knowledge and Poetics from Mesopotamia to BuzzFeed 01Cole Young, Liam. List cultures: Knowledge and Poetics from Mesopotamia to BuzzFeed, Amsterdam University Press, 2017. the analysis of the digital music top charts carried out by Cole Young goes on to highlight the list function as a carrier of culture. There is no cultural field that is more amenable to listing activities than the modern music industry: these structures of order are used within the industry to organise information and communicate information between producers and consumers. How do knowledge and cultural activity circulate within the field? Top music charts are indicators of the popularity of music at a given time. They stand as a reflection of musical current events and thereby of musical culture. Therefore, the list becomes much more a container than content. It carries information and stands through time and through different contexts. In other words, the list can be read and understood much in the same way as a template works: a shaped structure used as a pattern for processes such as cutting out and shaping. And as any container, its meaning adapts itself to the content it contains.

It seemed essential to choose a more specialised area to focus my research on within the wide domain of the list. If not, it would be too easy to get completely lost. The descriptive tagging system appeared as the right framework for this research. First, as a list, it tends to frame content into a set of words. Furthermore, it has the inherent feature of being able to be organised and manipulated in several ways, but most importantly, it is a proven tool in any online classification initiative.

This research combines an essay with a series of interviews, as two approaches to the same subject: how the structural tools of tagging influence the perception of our environment. Following this approach, the essay outlines all the different layers in play. The first part defines the terms and sets the framework of the research. The second part discusses and questions the relevance of human monitoring in the process of labelling. The last part focuses on how this process is displayed within the web landscape.

Some of the aspects will then be discussed, endorsed or nuanced by other external voices through the interviews.

In conclusion, starting from a simple subject of study, the present research aims to look at the tool of tagging as a critical tool: in its attempt of categorising everything, it dismisses some aspects by choosing others. Seemingly unimportant choices will determine what will be shown and what will be hidden, in other words, what will endure and what will disappear. These instruments therefore play a huge role in the construction of our culture today, and as such, greater attention should be paid to them.

This research started from a personal captivation with lists. Although part of the mystery still remains in this captivation, the remarkable ability of the list to structure and make sense of the world has been at the core of my fascination from the very beginning. Yet trying to find the edges of its intangible definition is a difficult exercise. Its seemingly simple structure hides a vast complexity of mechanisms. If the pleasure of studying the list easily outweighs the difficulty of getting hold of it, it is surely also because of the poetic potential the list has in itself, endowing it with an elegant subtlety.

‘In every enumeration there are two contradictory temptations. The first is to list everything, the second is to forget something. The first would like to close off the question once and for all, the second to leave it open. Thus, between the exhaustive and the incomplete, enumeration seems to me to be, before all thought (and before all classification), the very proof of that need to name and to bring together without which the world (life) would lack any points of reference for us. There are things that are different yet also have a certain similarity; they can be brought together in series within which it will be possible to distinguish them.’02Georges Pérec, ‘The ineffable joys of enumeration’, from Think/Classify, 1985.

Lists almost function as a looking glass to view the world. They highlight certain things and cover others. By attempting to fit everything into one place, they have to select and emphasize some parts of the information by leaving out other parts. When looking through this lens, the list outlines a finite frame to look through, clarifying and shaping the borders of each form it contains, assigning them a certain meaning.

Any type of structuring process requires defining a context into which it takes place. What is particularly interesting in the case of the list is that this context is invisible and only the reading of it can reveal it. Hence, all the necessary parameters of selection, hierarchy and presentation of the information have to be guessed from a combination of words. However, these parameters will shape how we will interpret it, by defining what to look at, how to look and where to look. It seems therefore important to me to investigate and question the structural and contextual systems that define our way of seeing, as pointers towards content.

The words within a book’s index will give a first impression of what the book is about. Because this labelling process is human-based, it must be guided by international rules to ensure a limited degree of subjectivity during the process. But, today with participative online platforms a broader range of potential actors are involved in the process of attributing meaning. From Folksonomy to Machine Learning taxonomies, different listing practices try to offer entry points into ever more extensive databases, and increasingly complex content. It raises an important question of authority and legitimacy, urging us to raise some fundamental questions: Who are the actors responsible for such decisions? And to what degree are their actions framed by methods and rules?

For its diversity in the range of potential authority figures and for its unique structure of dealing with quantity, offering key points in ever more complex databases, I decided to focus particularly on the tagging process, at the onset of web 3.0.

Defining the framework of investigation led me to this question: How do our structural tools of tagging frame what we look at and thus define what we see?

This research suggests a shift in focus, from the content to the structure, from the form to the skeleton, and from the overall to the detail. By directing attention to these underlying systems, it aims to give a better understanding of the dimensions of these tools deployed in order to structure.

These statements will be developed further throughout the text, but will also be reinforced by additional voices. I have spoken with Pierre Mohamed-Petit about translating living material into semantic bits Interview 01 and human monitoring Interview 03, exclusively in the specific context of photojournalism. I had a discussion with Olia Lialina about resisting alive systems of the web 1.0 Interview 05 and the use of tagging as a means of countering obsolescence Interview 02, exclusively within the specific context of archiving. This series of interviews ended with a discussion with Pierke I.S Bosschieter and Caroline Diepeveen on the interplay of technique and human selection Interview 04 in the indexing process and the display features of the offline and online formats Interview 06, exclusively in the context of book indexing. I will refer punctually to these interviews during my development, however they remain accessible at any time from the right panel.

This format illustrates an attempt to bring together various points of view and degrees of expertise for the same purpose: a better knowledge of these tools in use, giving a much more complete picture, so we can reflect on them.

Consider our environment as a landscape of boxes; in which any element can fit into one or several boxes. Yet before being categorised, each element taking part in our environment has been thoroughly identified and defined.

In order to have a definitive view of the world that fits into our field of vision, a process of rationalisation is needed, through the establishment of a common language. Dictionaries are language catalogues par excellence: they stand as reference sources containing what all the world is made of, providing a definition in all its aspects, from its form, its pronunciation to its function and its etymology. Such tools play a key role in the creation of an understanding of what is what. It assigns meaning to things, making them tangible and therefore potentially usable. Through language, any undefined element is streamlined into a semantic bit automatically called an item. In the following text, the word element will refer to anything that still needs definition. When something has been defined it will be called an item. Once the elements have been defined, the generic word world previously used in the broadest possible sense will be substituted by the much more precise term environment, henceforth conscious of the make-up of our surroundings.

Once defined, these items need to be categorised. By definition, an item is a ‘unit part of a list, a collection, or a set’.03Lexico Oxford online dictionary. [Online]

Available here There is the notion of belonging to a whole, introducing the concepts of hierarchy, order and links between them. Any item belongs to a broader group of items, the same group belonging to a bigger set. It creates a whole infrastructure of information and shapes boundaries between groups of items. This is where the structure of the list comes into play. Etymologically, the word list04Online etymology dictionary. List. [Online]

Available here is related to the notion of border, which is very much in line with the pre-established definition of the list as a structural container. If you think about any list regardless of the purpose it is made for, it functions as a box whose structure makes it a remarkable tool to describe something in the most exhaustive and most definite way, rendering its components into a set of words. The dutch word lijst05Van Dale dictionary. Lijst. [Online]

Available here also refers to the frame around a painting or a photograph. The frame concentrates the view on what is inside and obscurs the rest. By this definition, the list is almost literally a looking glass, a window on the world.

Thus, when we look at List of lists of lists06Wikipedia.(2003) List of lists of lists. [Online]

Available here from Wikipedia, the submitted innumerable data gives the impression that the whole world has been cropped into that frame. Everything seems to be inside, from the list of minor planets to the list of ancient kings. Everything is so well orchestrated, with countless boxes to classify and order data in, without leaving anything on the side that the completeness of this huge list seems indisputable. Although it is practically certain that not everything is truly inside, the illusion that it is would be sufficient to attribute to the list a primacy in any effort to categorise a content. image

It seems essential to clarify the understanding of what is meant by the term list. Think of the list as a mold: a mold is commonly defined as a hollow form shaping a substance.07Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

Available here This general definition fully echoes my own understanding of the list. The substance, which can be understood as any element from an original content, will take shape through the structure of the list, emerging as semantic chosen bits Interview 01.

In that sense, any listing process implies a selection. Museums were one of the first expressions of an already established selection system. From an infinite reservoir of potential elements, the finite form of the list can therefore only contain a finite number of items.

Today the most used tool to unlock online lists is the tag. Because the term tagging stands for a variety of activities, it is important to recall that this research will strictly confine itself to the investigation of descriptive tagging, rather applied to a text or to an image, leading to the creation of micro digital lists. Thus, the tagging process will only refer to the elaboration of a series of keywords to classify, order and categorise, making a web-object08The term web-object will refer to any element in the digital context. traceable in a database. As the ultimate tool of online referencing, the tag acts as a point to refer to when facing within increasingly complex databases. By assigning a tag to a web-object, the resulting word becomes an identical keyword. By doing so, it immediately ensures online visibility.

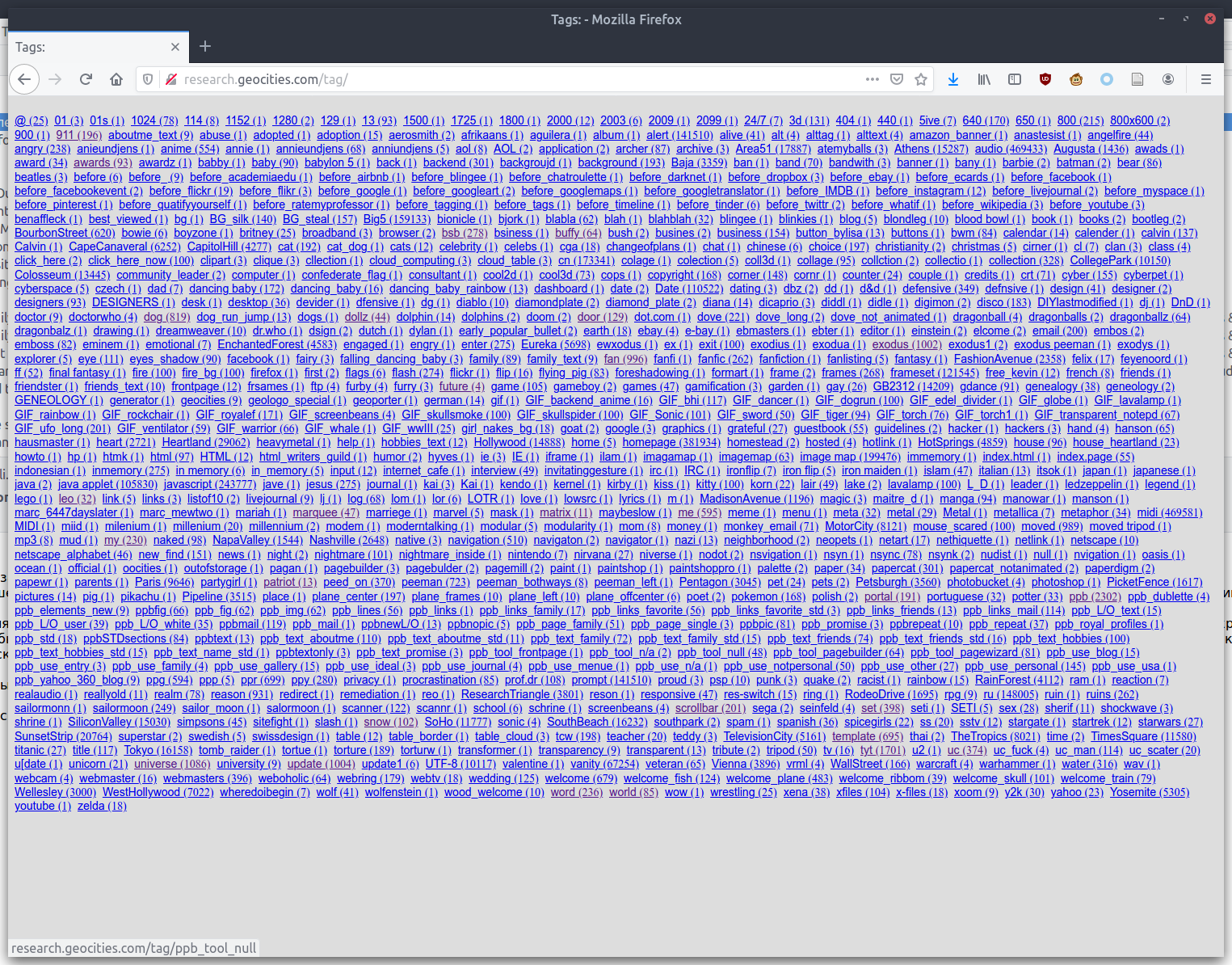

The net artist Olia Lialina, through her undertaking of referencing obsolete sites from the old Geocities.com, attributes to each item a tag, and therefore an identity.09One Kilobyte of Terabyte Age, Olia Lialina.

Available here and here.

For now, only these two platforms exist but she is working on a new platform that would become available to the public in the future. She will integrate her current work of classification of each web page. This personal approach brings out the importance of referencing items in the context of the web: she makes these forgotten web pages visible and present on the web again. In other words, tagging guarantees they survive online by inscribing them in the current online feed, making them traceable again. image

This selection process immediately excludes other interpretations and readings of the original content and determines one or more selected ways of looking at it, depending on the strategies determined by the platform in which the labeling process operates.

One of these is to be as exhaustive as possible, thinking of all of the most common possible interpretations: this is the case with platforms such as Getty, Shutterstock and Alamy, but more broadly any platform that needs to generate income. This strategy has an overall focus, trying to build the biggest boxes of images as possible by choosing generic broad words rather than specific ones. Hence, it will ensure a better visibility by the largest audience, increasing the chances of an element being found by several potential keyword searches.

The other strategy proposes a focus on the particular rather than the general. Within her collection of web pages, Olia Lialina uses the tagging system as a way of maintaining the individual specificity of each image, using the most accurate keywords to define what the image is about. Such a system will ensure the image to be found for its uniqueness and its particularity, even if it will decrease its chances of being found in a search based on more general keywords.

Thus, we can already see that the context in which the listing process is done strongly influences its parameters of action, which turns the list into a malleable tool.

The list has a privileged place in our society. So far, it has been in constant use for more than 5000 years and is implemented in an infinite number of environments. Where systems of order surround human society, the list is there. Over time, it has been adapted, modified, but today, it still stands. And this is the power of the list, it adapts itself to the context it lives in with incredible ease. Thus, it is worth and valuable to make these structural tools, usually largely overlooked, an object of analysis. The research of Liam Cole Young seems to follow the same approach, by tracing the list from a three-pronged approach. Through a historical exploration, he proposes we look at the lists from the past, present, and future, tracing the list from the ancient list of Mesopotamian kings to the very new digital lists the web 2.0 is teeming with. A clear future perspective is enunciated: “The upshot is that lists simultaneously challenge extant knowledge formations but also create new ones by inscribing new modes of organization and classification, which amount to new ways of seeing and doing.”10Cole Young, Liam. List cultures: Knowledge and Poetics from Mesopotamia to BuzzFeed, Amsterdam University Press, 2017.

He continues to argue using the significant example of popular music charts: “Popular music is a field where lists are particularly easy to trace, and where they receive a relatively unusual amount of critical attention. We can learn from this attention and export it to other realms where lists are no less present but much harder to observe.” What makes the list a specific focus of attention in the context of popular music is its close relation to culture. Compiled in 2009, Bob Mersereau’s Top 100 Canadian Singles brings together one hundred singles which were considered popular by an audience of 800 people, consisting of both producers and consumers. It freezes the tastes and preferences of one period in the present time but also makes it past oriented as a record of a time period and yet future oriented in that it will potentially become a historical document used at some point in the future. Therefore, the same way Cole Young looked at how lists operated in the past to understand their position in our contemporary society, can a better understanding of how lists operate today expand their scope of action for the future? Showing not only what a list is about, but what a list can be. Because if referencing serves the purpose of preservation, Olia Lialina also uses these technical tools as a means to ensure them future visibility Interview 02. She describes a screenshot of a web page looking at what is currently valuable to record, but she also thinks about which tag might be the most relevant in the future. Lialina is going through this process without knowing how the tools and the digital environment will evolve.

So, if online tagging has the power to make web-objects visible or invisible based on its good or bad categorisation, it is essential to question who can have such a power, who is in charge of such a task.

The web 2.0 has led to the emergence of new collaborative forms of tagging. In 2004, Thomas Vander Wal established the term of Folksonomy,11Technopedia. What is Folksonomy. [Online]

Available here as a combination of folk and taxonomy: Folksonomy is a classification system that enables users to assign tags to web content (e.g. websites, pictures, documents). It is now a common feature of most social media and web 2.0 platforms. Through this crowd classification system, the perpetuation creates an understanding in our collective mind of which keywords are assigned to what type of items. Over time, this practice of social tagging gave rise to more and more platforms acting in various contexts, from Shutterstock for visual content, De.li.cious for Internet bookmarks or Twitter for social posts.

But it seems important for me to consider whether online referencing can really be part of a collaborative effort. At first sight, it seems to be challenging to make the following two distinct strategies coexist: freedom in the choice of keywords and the system of classification of images by search result, via the analysis of the popularity of images by number of clicks. In what kind of current online contexts is this classification system used? And within these contexts, does this freedom given to the users require a monitoring mechanism or can they be fully responsible for assigning keywords to any element?

If Folksonomy works towards a democratization of the tagging system and hence participates in the development of the web and the referencing of any web object, it also operates in a much more professional and controlled digital space. Today’s platforms are becoming more and more complex and systems are being more and more automated, which I believe already fixes limits on the scope of action of individuals.

In recent years, as guides and accelerators of the process, many programs have been developed for the users of stock images platforms, such as Stocksubmitter or Shutterstock Keyword Tool. Since 2007, Shutterstock has been complemented by a Keyword Tool interface, accessible from the ‘submit’ page. Therefore, there is a double filter system. On one hand, any content with its keywords that is submitted on the platform is subject to validation before being added in the image catalogue. On the other hand, the keyword tool in place suggests which keywords to add. After the user has uploaded his image, the tool proposes a series of images it considers to be similar. The user has to select the 3 most relevant images, which will generate a whole list of keyword suggestions, presented from the most relevant to the most optional. Therefore, we quickly understand that the promise of a collaborative system, from the folk for the folk is deceptive and illusory in that specific context. If an image is mistagged, it can directly become invisible. Thus, the freedom given to the users does need a supervisory mechanism to guarantee a proper functioning of the overall system, resulting in a pertinent search by keywords on the interface so the images can be sold. On such platforms, these online individuals are considered as users, putting them directly in a position of contributors, in the service of, and following the established rules and system of the company. Integrating individuals is a noble goal indeed, but it remains difficult in the narrow context of stock images, where the success of the system depends largely on the common value of the keywords.

In the era of the web 3.0, the automation of the process of tagging is becoming more and more common. Artificial Intelligence (AI) research into image recognition has risen exponentially in the last decade. One of the stated aims of AI is a better understanding of the world around us. As such, an increasingly large proportion of human reality is now defined by algorithms. It appears essential to me to mention the emergence of Machine Learning taxonomies, where tags are generated by an algorithm that will analyse the content to automatically generate tags.

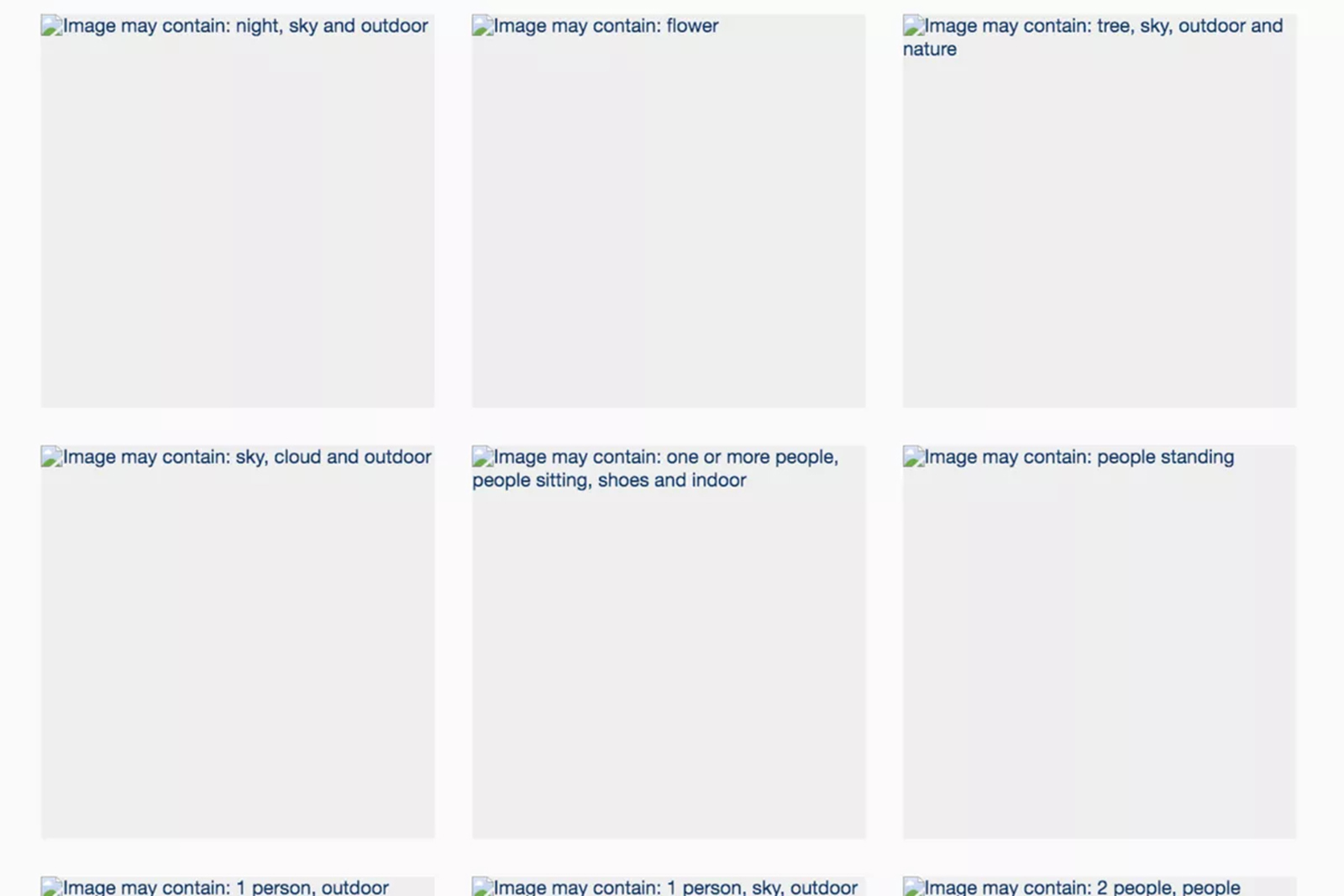

Think of these grey squares appearing on the screen when the internet connection isn’t good enough to show the images on Instagram, or Facebook. Lines of text appear at the top left corner of the image describing the input and giving actual keywords on what it is. image

If these keywords are only visible in case of a dysfunctional connection, it shows the capacity of these underlying algorithms to read images. Because their reading of the image appears very straightforward and descriptive, the labelling process results in very generic and meaningless words. This is precisely what happens with stock images platforms mentioned above.

The ESP game12Human computation. Youtube. [Online]

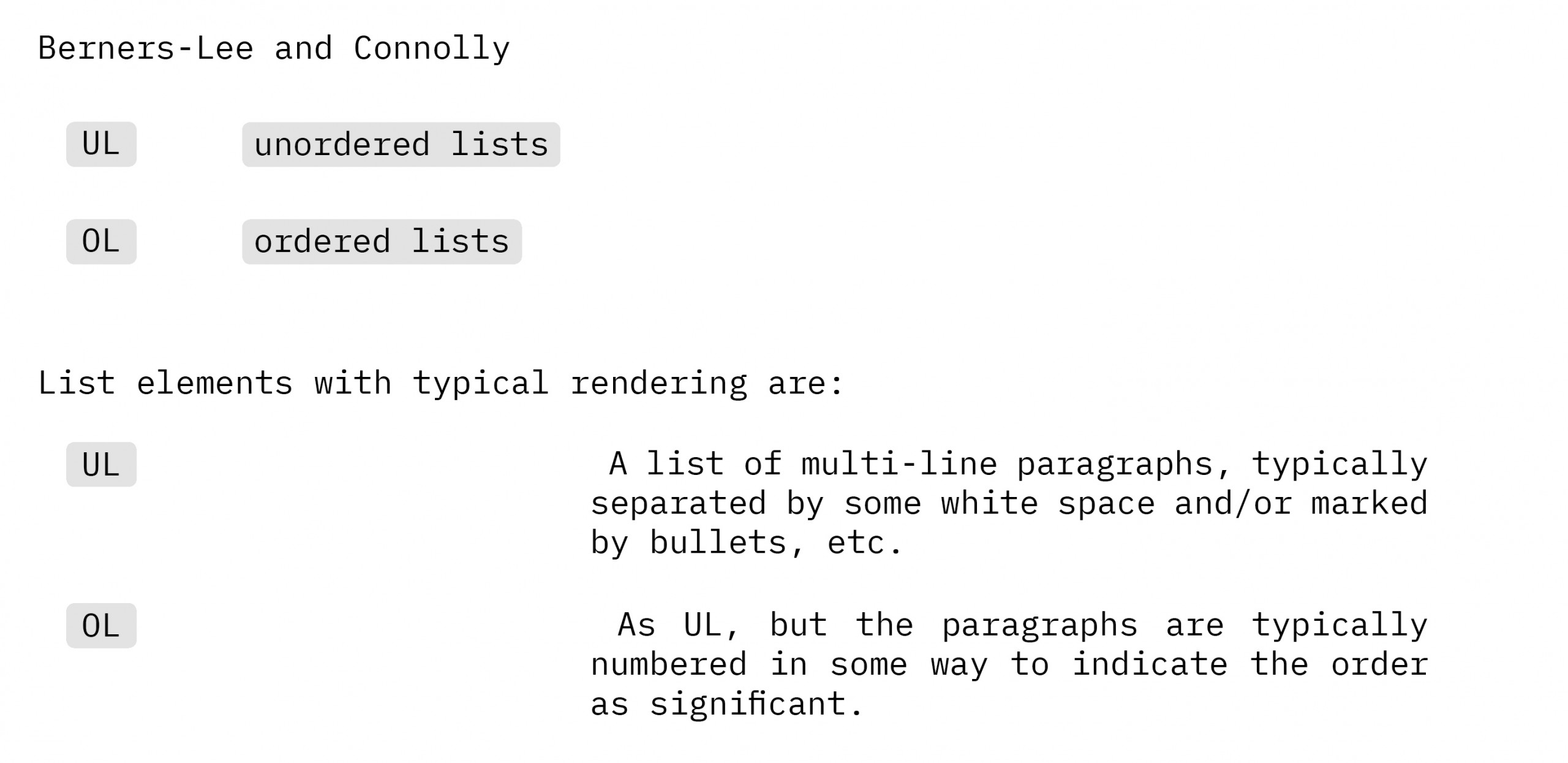

Available here presents itself as a meaningful example of how human collaboration in the labelling process can be fully deployed as an added-value. Created by Luis Von Ahn in 2003, this online platform uses human computation to radically accelerate the referencing of images on the web. A pair of users each presented with the same image but on separate screens, type descriptive keywords until they find a common identical keyword for the image. Each time they agree on a keyword, they get a certain number of points. To make the system more efficient, the principle of taboo words has been created. Taboo words are keywords that have already been agreed on by two previous players, so the current players cannot use them when trying to agree on a new keyword for that particular image. Because the platform does not need to be profitable, it frees every individual from any pre-established underlying strategy. image

There is potential value in using the human eye in tagging. The exciting aspect lies in how these structural tools, with their remarkable descriptive ability, and in all contexts where the tagging system is applied, lead to a certain description and categorisation of all the elements that surround us. Consciously or not, the context establishes an intention. This led me to ask myself who: who has the authority to do so? And for what purpose?

In some instances the misinterpretation from the algorithms on social media platforms makes us smile, in other instances it may have more important consequences depending on the context. Sometimes, labelling requires Interview 03, assigning authority to a specific chosen individual. Rather in the context of photojournalism, where the subjective view of the photographer adds a proper understanding of a situation, or in the context of book indexing, using human knowledge Interview 04, technicality and capacity to fill in the gaps. From a more general perspective, because labelling is a way to delineate into which new set an item is categorised and therefore perceived, human monitoring will only increase the control over this process.

One of the other parameters that plays a primordial role in how a set of words is read is the order in which they are organised. The concept of hierarchical organisation is also embedded within the structure of the web. In the early days of the web, a distinction was already made by computer scientists, Tim Berners Lee and Daniel Connolly13HTML: A Representation of textual information and Meta Information for retrieval and interchange, 1993. between ordered lists (OL) and unordered lists (UL) within the HTML syntax. image

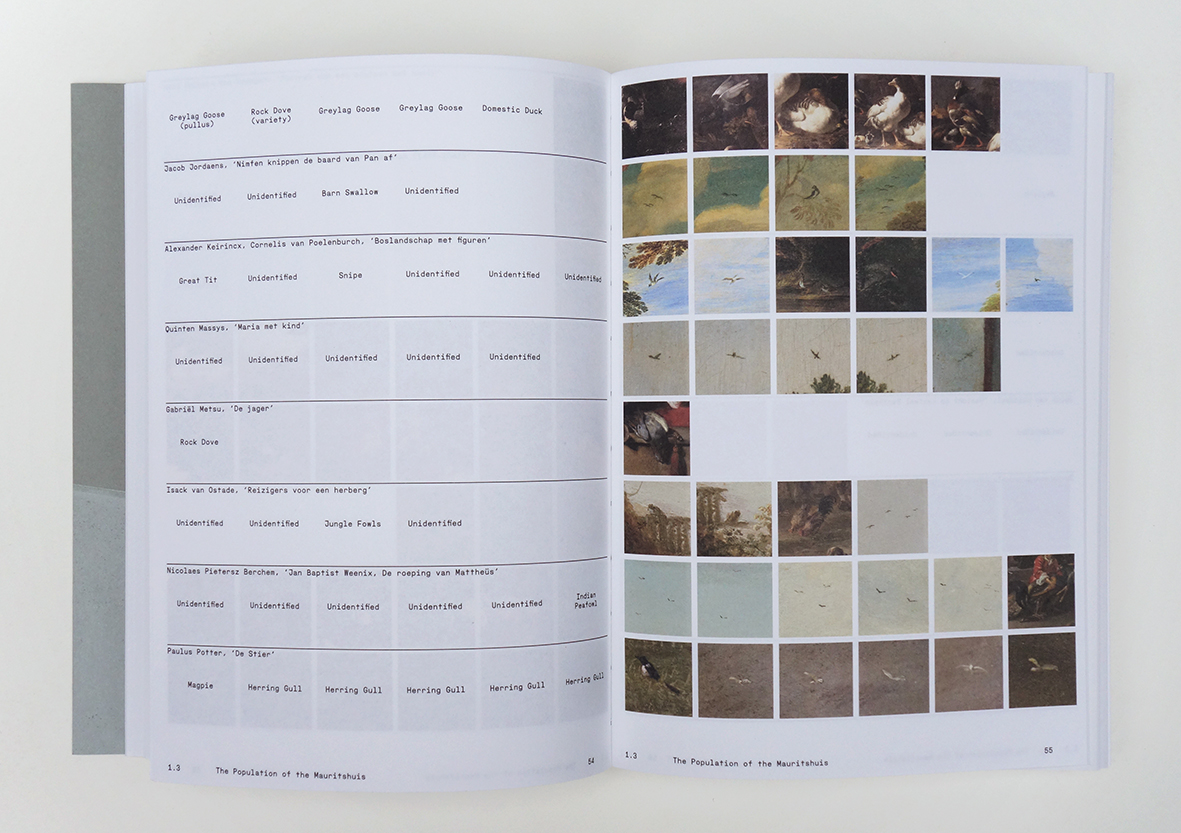

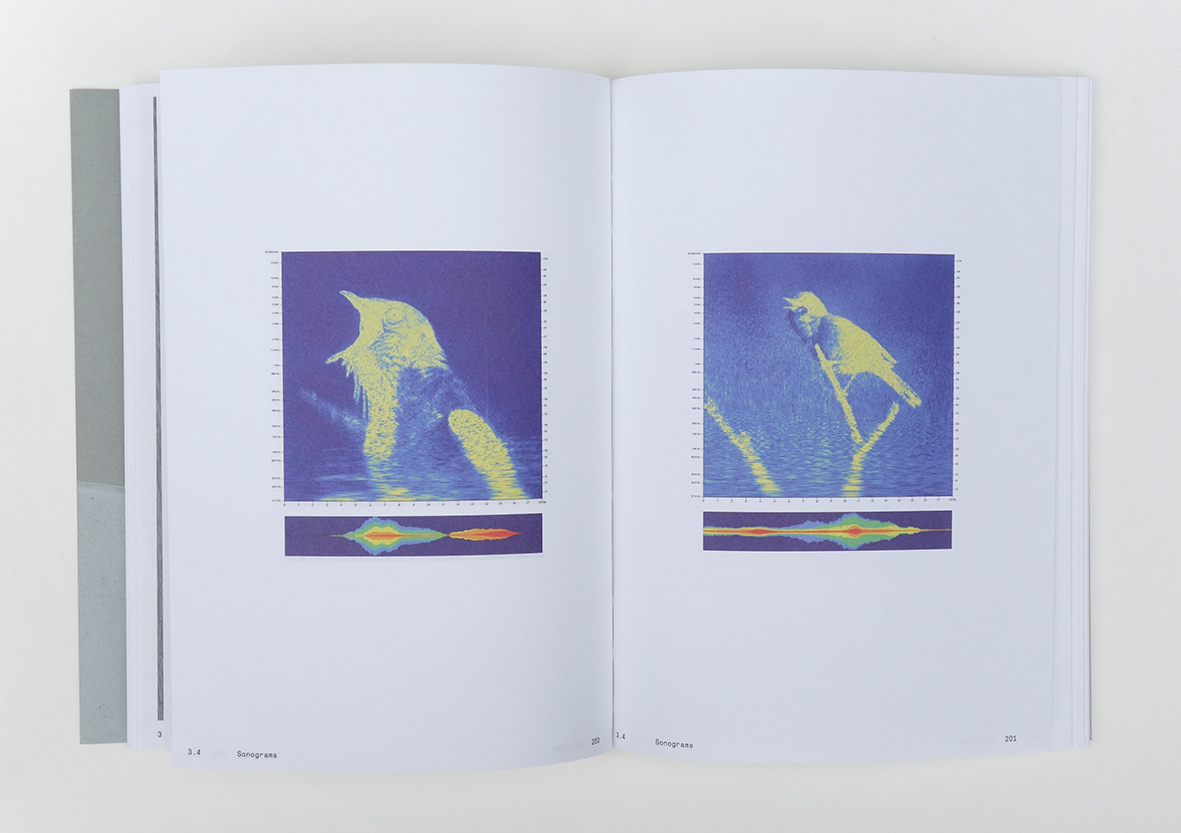

Any attempt at labelling organises items into a whole by following a certain logic, in compliance with a pre-established order. The book Ornithology by the duo of photographers Anne Geene and Arjan de Nooy combines within the same book both a scientific and a photographic study of birds, using content from their own photographs to paintings from art history. From the very first pages, the table of contents of the book clearly suggests an original excursion through the imagery by the combinations it draws through the chapters. The chapter ‘Bird Geometrics’ contains photographs of bird choregraphies while the chapter ‘Sonograms’ is entirely reserved for scientific bird sonograms. Anne Geene outlines the main thread of her work: “my work is about objectivity and on how you can give a photograph all kinds of meanings. How you can shift with contexts and information. I see photography primarily as an information carrier that can be used to tell different stories.”14Mondriaan Fonds. Interview: Noor Mertens and Anne Geene. Extract from Prospects & Concepts 2016.

Available here Anyone who looks at a subject with an original outlook runs the chance of making discoveries that others, scientists in that case, carelessly ignore. image

If this project takes advantage of the potential of order as a means of creating new associations, the order remains a parameter that we are rarely aware of. For instance, we instinctively use the alphabetical order for the vast majority of documents. As a universal agreement, it is taken for granted, excluding the possibility of being questioned. Whatever approach is chosen: they always incorporate a certain perspective. Ordering things by frequency will automatically put the focus on the most common items, whereas an alphabetical order provides visibility also to more specific items. Therefore, as much as a selection of specific words influences our way of seeing, the way of ordering will influence how we apprehend and interpret the information. According to the sociologist Douglas Harper, the latin etymology of the word index,15Harper, Douglas. 2017. “Index”. In Online Etymological Dictionary.

Available here meaning listing items following a specific order, refers to “one who points out, discloser, discoverer, informer”. The order directs, but it suggests and does not impose. And this is where my fascination for the list structure originates: the order subtly suggests a message. It automatically adds a further layer of meaning by the way words are put together. But if the order directs, it is not the only parameter that influences the reading and experience of a list.

“Each medium should be seen as a constructed frame that can oscillate between being regarded as a transparent window (between people, or between users and texts) and a reflecting mirror (drawing attention to the media technology and design itself).”16Fornäs Johan, Becker Karin, Bjurström Erling, Ganetz Hillevi. Consuming Media, Berg Publishers, 2007. This metaphor introduces the notion of reflectiveness in the discourse around user-computer interaction. If it portrays an interface as a window, fading away in the background so the user does not notice, it also suggests to render the interface visible and reflective to the user. Today, the idea that users should not even notice the presence of an interface has become widely accepted. If we look at the current web, it is moving towards a maximum simplification of interfaces, developing ever more invisible and ‘transparent’ interfaces. However, by making these interfaces transparent to the user so that they fade away for a simplified online navigation, it makes the underlying structure of the web opaque. For now, any technical tool and any structure ensuring a proper online experience blends into the digital scenery. They lurk under the visible facade presented to the user: if we think about any online platform using tagging as a tool to organise its content, this online indexing process is almost never visible. However, in order to reflect on our structural tools and on the use we have of them, they need to be visible. For now, one of the only sets of tags that are made accessible and browsable are the ones from stock images platforms. As they not only have to be successful but also profitable, the resulting tags are poorly exploitable and not very meaningful in my argument: the subtle potential of the list to suggest, to say more, in line with Perec’s approach, is reduced to its minimum in this context.

If these structural tools are not visible, it does not mean that they are not present. They are the tools that give shape to the visible facade the user navigates in and to make the web space what it is, how we know it as users.

In both offline and online contexts, the main task of structural tools is to label a series of items in order to make them accessible from a certain place and at a given time. But if the task remains the same, this modern online space in which the listing tool operates, seems much more complex. The pressure to be and to stay visible is more present than ever. And being visible also means being distinguishable. It is in this context that the new form of listicles has appeared, as ultimate semantic bits of information. Much of the success of platforms like BuzzFeed is entirely based on these concise headlines, as eye-catching tools: the list is narrowed down to its function of being able to provide a clear, direct, concise outline. These digital lists operate within a loop that enforces a view of the web as primarily a place for fast and concise information commodification. So, running into a more and more semantic language, the online space requires a semantic language to classify its content. If some platforms have evolved and adapted themselves to this shift in language, some others have disappeared, because these systems were not sufficiently semantic-based. If the approach of Olia Lialina with her project One Kilobyte of Terabyte Age is part of an almost nostalgic and fascinating perspective for an online space that seems far from how it is presented to us today, it also shows why these alive systems Interview 05 were intended to be deleted. By treating these pages as autonomous spaces of expression, granting the web page creator unlimited freedom, it also made them too specific to be inscribed and categorised in the already too semantic-based structure at that time. If the classification tools were already decisive at that time, they have become even more necessary today, since the digital space constantly continues to expand and diversify itself, becoming an increasingly saturated space. More than ever, tools like the tagging process are a means of navigating through this huge content the web box contains, making things findable by any potential user.

The format in which the information is displayed has a strong impact on how the information will be perceived and received. The tagging process can be seen as the digital representation of the indexing process Interview 06. But because they both operate under two different formats, the way they will be displayed and therefore the possibility to reflect on them differs completely. The online format implies a proper system of values, with specific uses. Indeed, the online space opens up new possibilities of navigation and interaction with information: the web appears to the user as a much more dynamic space than any offline format, where information gets sequenced and clickable through the screen. Any platform displayed online crops and adapts its content to fit the screen, in order to provide the best and easiest experience to the user. Supplemented by functionalities such as scrolling, this online navigation logic puts the focus much more on information being presented bit by bit, than information presented as a whole.

We can quickly observe a shift in the position the structural tools have within the digital environment. So far, the list has been commonly used as a means of reporting on a past or present moment, whether a historical moment, a current culture, or in a more prescriptive perspective, to evaluate what remains to be done. Recognised as a stand alone form and observed in its entirety, it would allow anyone to step back and reflect on it. This is where the main difference between an offline and an online environment lies: if the listing process is still locatable and present online, the result of this listing is no longer presented to us, directly eliminating any chance of interacting with it. Once created, established or generated, tags remain an unclassified and unpresented material. Moved to the back, the tagging result is dissimulated under the visible layer of the web. I find it fascinating as there is rarely the possibility to have a complete view of the content of a database on the web. There is no such dimension of space, or at least less and less. Only the tag clouds on platforms like Flickr were providing a visual summary of the content of the database. They have almost disappeared now: the tags can only be observed one by one. Although only the most popular ones were displayed, these visual word clouds were considered as a helpful tool for any information seeker to get familiar with the platform, providing them a general idea of what the content was about, itself suggesting another way to access, to dive into the content and make discoveries.

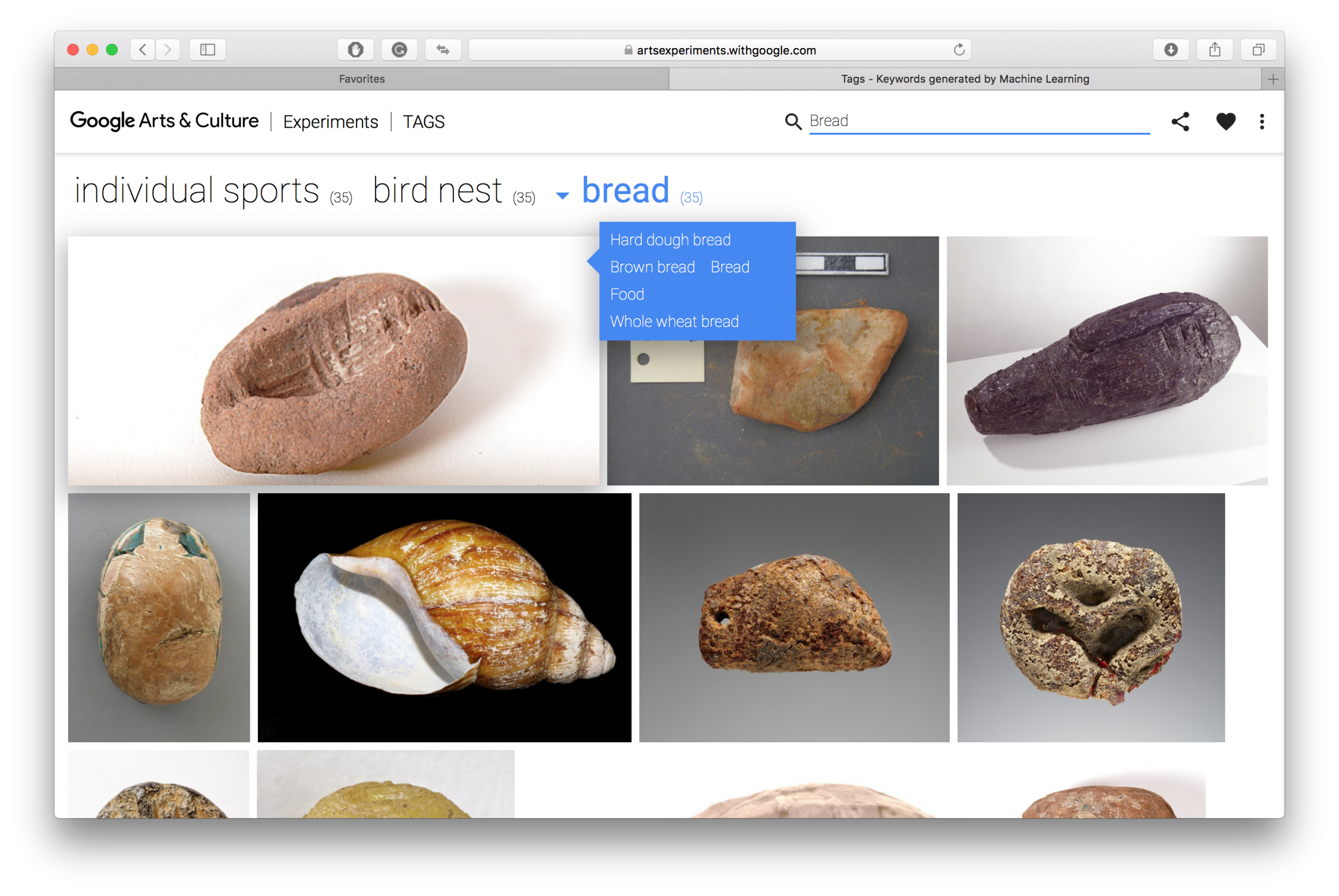

Practically all the online databases, regardless of their purpose, never show the tag as an entry point into the content. Google Experiments: Tags17Experiments with Google: Tags. Could computers help identify artworks? [Online]

Available here is one of the rare examples displaying all the tags together from the same database. This project acts as an experience where the content is not displayed in a way we are used to. From the front page, the user is invited to browse through the collection of artworks by these identification tags, from the most common to the least common. Navigation by tags creates unexpected connections between two items of the collection, displaying them in a completely different order than the one we would be used to in a museum for example. Enabling the comparison, this display ensures the list to fulfil its primary function of reflection, by bringing together individual items in a coherent whole. image

I believe that the potential of the list rests in keeping its edges visible. To keep its main function of revealing how we organize and describe the world around us, the digital list must still be able to be presented as a whole. I find it regrettable that the result of the tagging process is almost never shown. If the tagging system is an indexing process, it is for now never presented as an index. It would reveal much more if they were re-organized and made visible, by treating them as lists. The tag is a representative carrier of the evolution of our relation to classification which itself reveals how we describe the world around us, and therefore how culture is constructed. It is in this direction that my project will be developed, by reinterpreting, reclassifying and re-presenting, these potential unedited lists that are the tags. By reversing this engineering, bringing the tags from the background to the visible surface of the web, it would show how this simple daily tool of listing suddenly appears as a descriptor of our daily world, without us being aware of it and its consequences.

This research proposed a close focus on the structural tools used to organising our environment, by making them an object of analysis in the first place. It intentionally shifted the focus on the structure to first create a clear understanding of how the infrastructure of information is shaped and constructed through the use of these tools. If the first aim of this research was to raise awareness on how they work, it also had, on its own scale, the will to question them.

The first focus of the research was to analyse what any attempt of streamlining would imply, by defining any element, part of an undefined world, into an item, part of a defined environment. Once named and classified, these items are rendered understandable and exploitable. Their categorisation ensures them to be usable in the present environment. It may also be a means to ensure them a future visibility, if we consider Olia Lialina’s approach, which tries to define identification words that might also be relevant in the future.

The notion of selection has also been discussed: any inventory process implies a labelling process, by selecting some elements while neglecting others. The list as an instrument of categorisation focuses attention on the selected items it contains within its finite frame while dismissing others. By summarising data into a set of semantic bits, the labelling process acts as an interpretative layer. If some strategies of labelling automatically discard other possible readings of an element by choosing only one possible interpretation, some others, like those discussed with Pierre Mohamed-Petit, may enable a more extensive reading by building several potential stories around the same item.

From Folksonomy to Machine Learning taxonomies, the range of possible actors involved in the online labelling process has expanded, which raised the question of authority: who is in charge of this crucial task. Human monitoring emerged as a significant added value to the result of a labelling process. This statement has been strongly substantiated by the point of view of Pierre Mohamed-Petit: specifically in the context of photojournalism, an accurate tagging on photographs is crucial in order to ensure a proper destination and utilisation to the image. Pierke I.S. Bosschieter and Caroline Diepeveen took this thought a step further, leading me to look into contexts where the human eye is as equally essential, but whose manifestation is more subtle. Indexing a book requires the ability to transmit correct and easy information in the most neutral way: it implies being able to rely on human knowledge, as experts rather than on personal opinions, as individuals.

The economic model on which many platforms are based emerged as a major influencing factor in the result of the tagging process. Every economic motor has to fulfill several demands for the proper functioning of the platform. The success of the system depends largely on the common value of the keywords attributed to the content for its correct referencing and therefore for its proper distribution to the users on the platform. A general description will therefore be preferred to a particular description, increasing the chances of the items being found by a variety of potential keyword searches.

The last focus of the research was placed on the use of these structural tools in the digital age. The shift in the format from an offline environment to a digital environment seemed to assign a new position to them. The tagging process is more than ever needed online to categorise any web content, translating it into a semantic-based language and ensuring it continues being visible. By looking at the current position of these tools within the landscape of the web, it questioned their visibility: are they presented to the user, and if so, how? Taking the specific example of the both print and online index Pierke I.S. Bosschieter and Caroline Diepeveen have collaborated on, it confirmed how much the format influences how we interpret information. On the web environment, the result of the tagging process almost never appears on the visible layer of the web. However, if our structural tools of labelling define what we see by framing where to look at, it means that a comparison between the items and an analysis of the labelling result as a whole should always be possible, regardless of the context or the format in which it operates. Making visible the tagging result would reveal much more on how we describe our daily world. What we select to label and to put into boxes in order to keep it intact thereby defines what will and will not take part in the making of our culture.

If this research started by analysing the labelling process from an offline perspective, the future project will exclusively focus on the online environment. Tagging tools are shaping a world inside the computer. They label any web-object and give them a specific place on the visible scene of the web. But this constructed reality takes shape into a flat, clean and simplified online facade. For now, the underlying fabric of tagging does not reach the polished surface of the web. Victoria Vesna argues: “People working with computer technology have to think of the invisible backbone of databases and navigation through information as the driving aesthetic of the project”.18Vesna, Victoria. Database Aesthetics: Art in the Age of Information Overflow, University of Minnesota Press, 2007. This approach reflects the intentions of my role both as a designer and as a user of these hidden infrastructures within this research and the forthcoming project: it appears essential to me to focus on the machinery by showing the process now lurking behind the scene, which would give more hints on how information is shaped. While the investigation of these categorisation instruments may at first glance seem fairly simple, a thorough analysis revealed many more layers and consequences than imagined. It reinforced the urgency of investigating them further by giving them greater attention. By unveiling the hidden engineering and the parameters of the machinery, it would provide new perspectives of looking at how information is processed, presented and perceived.